"A building being built is not yet in servitude. It is so anxious to be that no grass can grow under its feet, so high is the spirit of wanting to be. When it is in service and finished, the building wants to say, 'look, I want to tell you about the way I was made.' Nobody listens. Everybody is busy going from room to room.

But when the building is a ruin and free of servitude, the spirit emerges telling of the great marvel that a building was made."

LOUIS I. KAHN

quoted in Architecture + Urbanism; January 1973

But when the building is a ruin and free of servitude, the spirit emerges telling of the great marvel that a building was made."

LOUIS I. KAHN

quoted in Architecture + Urbanism; January 1973

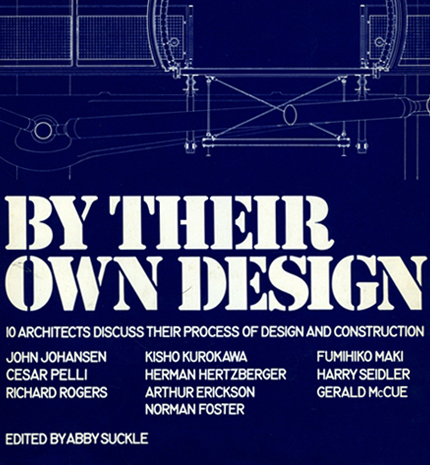

INTRODUCTION

For as long as there have been buildings the questions of what they look like and how they are constructed have been almost inseparable issues in the process of creating architecture. While in theory design is completed before construction, more often than not, considerations of available building materials or technologies have a great deal of influence on what is designed.

In the past, traditional methods of construction and available materials usually defined what was possible to design and build, but now, with sophisticated engineering and a vast array of new materials, the choices to be made are numerous. Just what does shape our buildings? The debate is a silent one, a dialogue which each architect conducts between the ideas in his head and the realities of existing construction materials and techniques.

The answers, and there are more than one, lie somewhere in the gray area defined by the two extremes: those who design formally beautiful compositions without any concern for the realities of how they might be built and those who build simply in the most expedient and inexpensive manner without regard for what buildings look like.

The ten internationally known architects represented in this book, all with major buildings to their credit, have each faced these two questions in every building they have designed and built. Each, in turn, describes his own concerns, both artistic and pragmatic, as they relate to the process of designing and constructing one or more of his buildings. The approach of each of these architects differs tremendously: from Norman Foster's space-age technology, so visible in the taut skins of his buildings, to Richard Rogers' mechanistic and structural gymnastics in the design of the Center Beaubourg; from Arthur Erickson's use of structural elements to create powerful sequences of space to Harry Seidler's predominant concerns with exploring various methods of construction.

Others who analyze their own work process include John Johansen, Gerald McCue, Herman Hertzberger, Fumihiko Maki, Cesar Pelli and Kisho Kurokawa.

While it is clear that there is no single answer to the relationship of design and construction, the points of view expressed in this book show just how divergent the possible approaches are. Their words as well as their work are provocative reading for architects, students, and those interested in the built environment.

In the past, traditional methods of construction and available materials usually defined what was possible to design and build, but now, with sophisticated engineering and a vast array of new materials, the choices to be made are numerous. Just what does shape our buildings? The debate is a silent one, a dialogue which each architect conducts between the ideas in his head and the realities of existing construction materials and techniques.

The answers, and there are more than one, lie somewhere in the gray area defined by the two extremes: those who design formally beautiful compositions without any concern for the realities of how they might be built and those who build simply in the most expedient and inexpensive manner without regard for what buildings look like.

The ten internationally known architects represented in this book, all with major buildings to their credit, have each faced these two questions in every building they have designed and built. Each, in turn, describes his own concerns, both artistic and pragmatic, as they relate to the process of designing and constructing one or more of his buildings. The approach of each of these architects differs tremendously: from Norman Foster's space-age technology, so visible in the taut skins of his buildings, to Richard Rogers' mechanistic and structural gymnastics in the design of the Center Beaubourg; from Arthur Erickson's use of structural elements to create powerful sequences of space to Harry Seidler's predominant concerns with exploring various methods of construction.

Others who analyze their own work process include John Johansen, Gerald McCue, Herman Hertzberger, Fumihiko Maki, Cesar Pelli and Kisho Kurokawa.

While it is clear that there is no single answer to the relationship of design and construction, the points of view expressed in this book show just how divergent the possible approaches are. Their words as well as their work are provocative reading for architects, students, and those interested in the built environment.

ARTHUR ERICKSON

Arthur Erickson received his Bachelor of Architecture from McGill University in 1950. He also won a traveling scholarship which enabled him to tour the continent, particularly Greece, Italy, and northern Europe. On his return he taught first at the University of Oregon and then at the University of British Columbia, where he became an associate professor in 1961. During this time he maintained a small private practice building mostly houses. He then received a fellowship to go to Japan and made the first of many trips to the Orient.

In 1963, in partnership with Geoffrey/Massey, he received the first prize in the competition for Simon Fraser University for an innovative scheme featuring a quarter-mile-long, glass-covered central mall surrounded by low-profile concrete classroom and laboratory buildings. When completed two years and $20 million later, it was considered by many to be one of the best of the new campuses of the sixties.

Since then Erickson has built widely. His work varies from an egg crate-like shelter built out of laminated recycled newspapers by the schoolchildren of Vancouver for the UN Habitat Conference, to the Canadian Pavilion at Expo '70, an intricate play of mirrored surfaces, to the recent courthouse/redevelopment scheme for the center of Vancouver, which is now completed.

Since the publication of By Their Own Design, Erickson's noteworthy contributions and innovative design work earned him the Gold Medal from the American Institute of Architects in 1986. The highest honor bestowed by the AIA, Erickson was the first Canadian to receive the reward. Prefacing this honor, Erickson received numerous awards and degrees, including gold medals from the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada in 1984 and the French Academie d'Architecture in 1986. He died in 2009.

CESAR PELLI

Born in Tucuman, Argentina, in 1926, Cesar Pelli received his architectural degree from the university there. He came to the United States to study at the University of Illinois in 1952 on a scholarship from the Institute of International Education. Shortly after receiving his Masters, he joined Eero Saarinen's office where he worked on such buildings such as the TWA terminal at Kennedy Airport and the Vivian Beaumont Theater at Lincoln Center in New York, for which he was the project designer. Pelli collaborated with such designers as Gunnar Birkerts, Paul kennon, Tony Lumsden, Warren Platner, and Kevin Roche in the Saarinen office during his ten years there.

When Saarinen died, Pelli left the firm to become director of design at Daniel, Mann, Johnson, and Mendenhall, a large corporate architecture/ engineering firm in Los Angeles. He received a Progressive Architecture Design Award for a project urban nucleus in the Santa Monica mountains. Two other buildings designed during this period- COMSAT Laboratories and Teledyne Systems- are notable for their linear organizations along a pedestrian street allowing for growth and change which form the organizational principle for his later award-winning scheme for the United Nations Headquarters and conference center in Vienna.

This building was one of the first projects executed after he moved to Gruen Associates as the partner in charge of design. While at Gruen, he also designed the Commons and Courthouse Center in Columbus, Indiana. Perhaps the first building of its type it functions as the town center, combining shopping and community facilities within one building. He was also responsible for the design of the U.S Embassy in Tokyo.

He was engaged in the design of the gallery expansion and condominium tower of the Museum of Modern Art, several housing projects, an office building, and his first single family house. In these projects, the use of spandrel glass, was pioneered as a economical cladding system.

Pelli taught consistently since 1960, first at UCLA, then as a visiting professor and critic at Yale. He was also its Dean from 1977-1984. He has published articles in A+U, Progressive Architecture and Architectural Record.

Since the publication of By Their Own Design,he designed The Petronas Towers, in Kuala Lumpur which were the world's tallest buildings until 2004. His office has been at the forefront of sustainability. For instance, "The Visionaire" in Battery Park City, NYC is a LEED-Platinum residential building. In 1995, the American Institute of Architects awarded Mr. Pelli the Gold Medal, in recognition of a lifetime of distinguished achievement in architecture. In 2004, Mr. Pelli was awarded the Aga Khan Award for Architecture for the design of the Petronas Towers, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

KISHO KUROKAWA

In 1960, at the age of 26, Kisho Kurokawa stepped onto the international stage as a co-organizer of the World Design Conference and a member of the Metabolism group. That group was formed as a way of trying to marry traditional Japanese design with modern architecture so as to accommodate growth and change. At that time he had completed his undergraduate degree at Kyoto University and graduate work in architecture at Tokyo University.

Most of his early projects were proposals for new forms of urban living, and they remained in project form. Typical was his Agricultural City of 1960, a framework of streets into which are fitted a checkerboard of communities all on the second level, freezing the ground for agricultural use. His ideas about architecture of the street were first realized two years later in the Nishijin Labor Center where a series of welfare offices were aligned along a pedestrian circulation spine. Since then he has built more than 35 buildings, numbering among them facilities as diverse as a drive-in restaurant, which is infilled into a megastructural space frame; several pavilions for Expo '70 in Osaka, such as the Toshiba IHI Pavilion, a motion picture pavilion with an amphitheater that rose up and down; and several new towns and government centers throughout the world.

He has published widely, writing 22 books on subjects ranging from prefabricated houses to action architecture. His diverse activities include running a think tank, the Institute for Social Engineering, and a monthly television show.

Since the publication of By Their Own Design, his major projects include The National Art Center, Tokyo; The Museum of Modern Art, Wakayama and the Osaka International Convention Center. He received the Gold Medal from the Academy of Architecture, France (1986), the 48th Japan Art Academy Award (highest award for artists and architects in Japan, 1992), and AIA Los Angeles Pacific Rim Award (first awarded, 1997). He was the first Japanese architect to become an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects.. Kurokawa was awarded The Chicago Athenaeum Museum International Architecture Award in 2006 (U.S.A).He died in 2007.

HERMAN HERTZBERGER

Born in Amsterdam in 1932, Herman Hertzberger received his architectural degree from the Technical University in Delft some 26 years later. That same year he opened his own office in Amsterdam and soon began editing Dutch Forum together with Aldo Van Eyck, Jacob Bakema, and others. He also started working on his first commission, a factory addition which is constructed on top of an existing building. This was followed by a dormitory, a building which attempts to break down the barrier between public and private. It also includes an indoor street on the fourth level where the married students' apartments are located. Each element such as the indoor street lighting is programmed to play as many roles as possible, an approach which is characteristic of his work. The block of lighting is at the same time a light fixture, a ledge for letters and groceries and a planter. Similar features characterize his Montessori school where, for instance, tiny childsize strips of sandpits are garden plots and make-believe houses, battlestations and treasure troves. He also 8 experimental houses which have been extensively and successfully adapted or taken over by their occupants to accommodate a diversity of lifestyles, in addition to the projects illustrated here. He has also worked on several town planning and urban renewal schemes.

His work has been exhibited and published widely. He has had articles published in journals as A+U, RIBA Journal, Domus and Architectural Forum. He has also taught extensively in America at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Columbia, in Canada at Toronto, and in Holland at Amsterdam and his alma matter.

Since the publication of By Their Own Design, his projects include Concert Hall Musicon, Bremen, Germany; YKK Dormitory, Kurobe, Japan and the Orpheus Theater, Apeldoorn, Netherlands.He has won numerous awards including the Richard Neutra Award for Professional Excellence; and 2005 Arie Keppler Award and the Oeuvre Award for Architecture of The Netherlands Foundation for Visual Arts, Design and Architecture.

JOHN JOHANSEN

In 1939 John Johansen received a Bachelor of Science from Harvard. In 1942, he acquired a Bachelor of Architecture and soon after a Master of Architecture from the Harvard Graduate School of Design. In the post-war years, he established his own practice. His early works were rather orthodox modern, which he has called "Renaissance by comparison with his later buildings." Gradually his buildings moved from very heavy monolithic concrete to a separateness of forms expressing distinct functional and structural parts and motivated by a greater concern for how buildings work to accommodate the needs of their occupants. The transition from what he calls his first "modern building", Clark University's Goddard Library, to his own house is startling. The former has been described as the "rear end of a Xerox machine" and was influenced by the organization of electronic circuitry, but still shows the lingering influences of Brutalism and Le Corbusier's la Tourette. Functionally, served spaces are distinguished from service spaces and circulation lines, a direct influence of Louis Kahn's work in the 1950s. The latter building, his own house, in contrast, is lightweight, flexible, improvised from industrialized catalog parts of steel and plastic, with rooms and platforms suspended or outrigged from a steel frame, with the possibility of permutation and change. This development led to his interest in the architecture of kinetics.

Johansen received two honorary Doctor of Fine Art degrees, has been President of the Architectural League of New York, and is a member of the American Institute of Arts and Letters. He was the recipient of the Medal of Honor from the New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects and the Honor Award from the national American Institute of Architects. He also was architect in residence at the American Academy in Rome. Johansen has been a professor at Columbia, Yale, and Pratt Institute and a visiting critic and lecturer throughout the United States and abroad. His buildings have been extensively published and exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and in Moscow, Berlin and Tokyo, while his articles have been published in the American Scholar as well as journals of the architectural profession.

Since the publication of By Their Own Design, his projects include Resort Hotels in Miami and NYC and the Maglev Theater. He was a speaker at the Sao Paulo Biennale '89, Brazil, on 'Cities of the Future'. In 2001, he became an Honorary Member of the Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland.

FUMIHIKO MAKI

Born in Tokyo in 1928, Fumihiko Maki received his Bachelor of Architecture from the university there in 1952. He then went to America to study at the Cranbrook Academy of Art and earned a Master of Architecture in 1953. The next year he acquired still another degree, this one a Master of Architecture from Harvard. He worked for Skidmore Owings and Merrill and Sert/Jackson before teaching, first at Washington University in St. Louis and then at Harvard. He has been teaching periodically since then at universities throughout the world.

Maki first stepped into the international spotlight in 1960 when he became a member of the Metabolist group. Inspired by Kenzo Tange's plan for Tokyo, the Metabolists were a group of architects who met to explore the future of architecture in Japan and produced a handbook for the World Design Conference of 1960. Maki's contribution was an article on the vernacular aesthetic of hill towns; it was an "attempt to create a total image of the vitality of the group while retaining the identity of individual elements." Several years later, Maki published his Investigations in Collective Form, in which he synthesized and developed these ideas. Since then he published an article entitled "Movement Systems in the City" where he argues the importance of incremental processes of built forms in existing cities, using various modes of movement systems as vehicles of such transformations.

Maki's work has been called "contextual" because of his obvious interest in developing systems that are coherent in themselves as systems and also part of a larger urban whole. This is typified by such buildings as Hillside Terrace Housing, which is notable for its hierarchy of public, semi-public and private spaces and volumetric vistas strung along a pedestrian circulation mall. Maki has always felt that the architect must design buildings to fit into the larger whole, and that technology must be a servant of human need. His search for industrialized components out of which to construct buildings that marry the best of industrialization with an appropriate scale are a part of this belief.

Since the publication of By Their Own Design, his projects include Spiral Building in Tokyo, 1985; Yerba Buena Center for the Arts; the Kemper Art Museum and the MIT Media Lab Expansion. In 1993, he was awarded the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize. He was the receipient of the AIA Gold Medal in 2011.

GERALD MCCUE

Gerald McCue was born in 1928 and received a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of California at Berkeley in 1951; he received a Masters in Architecture a year later. He then entered practice and built a range of building types from pirvate houses and subway stations to a marina and corporate headquarters. These works have earned over 30 design awards, including four national and seven regional American Institute of Architects honor awards. He has also conducted research, the most interesting of which are his studies concerning the effect of earthquakes on building components and ways of developing design procedures to accommodate earthquake hazards. This work has been published in a report, Architectural Design of Building Components for Earthquakes. He has also been interested in architectural programming and published a paper on that in 1978.

After having taught at his alma mater and serving successfully as a lecturer, professor, and chairman, he moved to the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where he held the position of chairman of the architecture department, associate dean and dean. McCue's conceptual concern with developing models for construction types without placing value judgements on any approach is a part of his concern about building well and building appropriately.

Since the publication of By Their Own Design, he became the Department Chair and the Dean of Harvard's Graduate School of Design (1980-1992).

RICHARD ROGERS

Richard Rogers was born in England in 1933. He received his Master of Architecture from Yale in addition to a few scholarships, including a Fulbright, which enabled him to study urban housing with Serge Chermeyeff. Following a brief stint with Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, to which some critics attribute his continuing interest in structural expression, he returned home to form his own firm in conjunction with his then-wife Su, and Norman and Wendy Foster. TEAM 4 as it was called, began by buildng houses which were frequently submerged into their often spectacular sites. These houses were traditionally constructed out of modest materials. They also began building loose-fit structure-oriented solutions, highlighted by the Reliance Controls Factory in Swindon, England. About that time TEAM 4 dissolved, and Rogers began practicing with Renzo Piano, most noted as a designer of many geometrically innovative light-weight shell structures.

During the twelve years they were together, Piano + Rogers produced a series of stunning loose-fit shed buildings constructed primarily out of standard off-the-shelf components borrowed from the automotive, shipbuilding and aircraft industries. Putting a building together like an erector set, they have tried to seriously deal with technology as a source for answers to such problem as material scarcity and quality control of the construction process. They have thought a lot about growth and change, which materializes in their work in the flexibility of the open plan, the demountable partition, the interchangeable facade panel, and the ever-extensible extruded section.

Rogers has also taught extensively at places like Yale, UCLA, and MIT and won numerous competitions including the new facility for Lloyds of London and the most famous is, of course, Center Pompidou.

Since the publication of By Their Own Design, he has received many awards. He was the 2007 Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate, recipient of the 1985 RIBA Gold Medal and the 2006 Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement (La Biennale di Venezia). He was knighted in 1991, made a life peer in 1996 and a Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH) in 2008. Some of his major projects include 3 World Trade Center, Lloyd's building, the Millenium Dome and the Madrid-Barajas Airport.

HARRY SEIDLER

Born in Vienna in 1923, Hary Seidler attended the University of Manitoba, where he earned a Bachelor of Architecture in 1944. From there he won a scholarship to do graduate work at Harvard University, which was just coming into flower under Walter Gropius. After receiving his Master of Architecture, he spent a year with Josef Albers at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Returning to New York, he worked for Marcel Breuer for several years and then briefly for Oscar Niemeyer in Brazil before emigrating to Australia to open his own firm.

Like most architects, his practice first consisted exclusively of private houses, which are most notable for their elegant structural expression. Unquestionably the best of these is his own split-level home built into a spectacular hillside site. Particularly innovative is his use of several upturned concrete channels that rightside up form the floors and upside down form the roof structure and sun protection. From the early houses he graduated to multifamily housing characterized by increasingly sophisticated split-level plans as well as to larger buildings. One of the most spectacular is the Australia Square circular office tower, a 50- story concrete structure engineered like much of Seidler's work by Pier Luigi Nervi. This particular building uses a single floor beam throughout, which is only possible in a circular tower and floor system. While the radial beams are poured, the precast exterior casings of the columns, which change shape as their load changes, were filled with concrete, which speeded up the construction process. This kind of integral marriage between structure and construction is typical of Seidler's work. Typical also is the sophistication of his precast concrete construction and his bold reaffirmation of the tenets of modern architecture. His work does, however, deal with the fact that architecture is about construction, which post-Modernism at least as it has been presented to date, has yet to seriously broach.

Seidler has won many awards for his buildings. Chief among them is the Gold Medal from the Royal Australian Institute of Architects. He has also taught at Harvard and the University of Virginia, lectured extensively and published a monograph, New Settlement Strategy and Current Architectural Practice in Australia.

Since the publication of By Their Own Design, he continued to build many projects primarily in Australia; however, his firm has also undertaken work in South East Asia, Central America and Europe, including a social housing complex consisting of some 850 apartments, 14 cinemas, kindergarten schools and shopping, fronting the Danube in Vienna.

NORMAN FOSTER

Born in Manchester in 1935, Norman Foster entered the university there and received his architectural diploma. In addition, he won the Heywood Medal and a traveling fellowship which helped him go to the United States and study at Yale. After earning a Master of Architecture there in 1962, he returned to England and established his own firm, first in partnership with his wife and Richard and Su Rogers and later with only his wife. He has taught extensively both in Europe and America, and is a past vice-president of the Architectural Association. He also serves as an examiner and member of the Visiting Board of Education for the Royal Institute of British Architects.

While his early projects were chiefly modest contour- hugging houses, Foster's designs began to veer in the direction of large- span loose- fit umbrella buildings, assembled out of dry factory-made components, which are also low in energy use. Over time the process- of deriving the program; defining its social goals finding the simplest, most efficient shed structure which affords the most flexibility for growth and change; and then erecting it- began to get increasingly more sophisticated. This can be seen in the progression from the Modern Art Glass Building to the Sainsbury Center. While both buildings have essentially the same sectional profile, the resolution of the exterior panel system, for instance, is far more developed in the latter building.

Foster's other projects include a highrise condominium/office tower/gallery addition to New York's Whitney Museum; a fabric- roofed, large-span structure covering a transportation interchange and urban complex for the London Transport Executive; a technical park for IBM in Middlesex; and a house for his own family in London where he experimented with glue technology borrowed from the aircraft industry.

Since the publication of By Their Own Design, his projects include the Beijing Airport; the redevelopment of Dresden Railway Station; the Swiss Re tower; an entire University Campus for Petronas in Malaysia and the Hearst Headquarters tower in New York. He became the 21st Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate in 1999 and was awarded the Praemium Imperiale Award for Architecture in 2002. He has been awarded the American Institute of Architects Gold Medal for Architecture (1994), the Royal Gold Medal for Architecture (1983), and the Gold Medal of the French Academy of Architecture (1991). In 1990 he was granted a Knighthood in the Queen's Birthday Honours, and in 1999 was honoured with a Life Peerage, becoming Lord Foster of Thames Bank.

"A building being built is not yet in servitude. It is so anxious to be that no grass can grow under its feet, so high is the spirit of wanting to be. When it is in service and finished, the building wants to say, 'look, I want to tell you about the way I was made.' Nobody listens. Everybody is busy going from room to room.

But when the building is a ruin and free of servitude, the spirit emerges telling of the great marvel that a building was made."

LOUIS I. KAHN

quoted in Architecture + Urbanism; January 1973

But when the building is a ruin and free of servitude, the spirit emerges telling of the great marvel that a building was made."

LOUIS I. KAHN

quoted in Architecture + Urbanism; January 1973

INTRODUCTION

For as long as there have been buildings the questions of what they look like and how they are constructed have been almost inseparable issues in the process of creating architecture. While in theory design is completed before construction, more often than not, considerations of available building materials or technologies have a great deal of influence on what is designed.

In the past, traditional methods of construction and available materials usually defined what was possible to design and build, but now, with sophisticated engineering and a vast array of new materials, the choices to be made are numerous. Just what does shape our buildings? The debate is a silent one, a dialogue which each architect conducts between the ideas in his head and the realities of existing construction materials and techniques.

The answers, and there are more than one, lie somewhere in the gray area defined by the two extremes: those who design formally beautiful compositions without any concern for the realities of how they might be built and those who build simply in the most expedient and inexpensive manner without regard for what buildings look like.

The ten internationally known architects represented in this book, all with major buildings to their credit, have each faced these two questions in every building they have designed and built. Each, in turn, describes his own concerns, both artistic and pragmatic, as they relate to the process of designing and constructing one or more of his buildings. The approach of each of these architects differs tremendously: from Norman Foster's space-age technology, so visible in the taut skins of his buildings, to Richard Rogers' mechanistic and structural gymnastics in the design of the Center Beaubourg; from Arthur Erickson's use of structural elements to create powerful sequences of space to Harry Seidler's predominant concerns with exploring various methods of construction.

Others who analyze their own work process include John Johansen, Gerald McCue, Herman Hertzberger, Fumihiko Maki, Cesar Pelli and Kisho Kurokawa.

While it is clear that there is no single answer to the relationship of design and construction, the points of view expressed in this book show just how divergent the possible approaches are. Their words as well as their work are provocative reading for architects, students, and those interested in the built environment.

In the past, traditional methods of construction and available materials usually defined what was possible to design and build, but now, with sophisticated engineering and a vast array of new materials, the choices to be made are numerous. Just what does shape our buildings? The debate is a silent one, a dialogue which each architect conducts between the ideas in his head and the realities of existing construction materials and techniques.

The answers, and there are more than one, lie somewhere in the gray area defined by the two extremes: those who design formally beautiful compositions without any concern for the realities of how they might be built and those who build simply in the most expedient and inexpensive manner without regard for what buildings look like.

The ten internationally known architects represented in this book, all with major buildings to their credit, have each faced these two questions in every building they have designed and built. Each, in turn, describes his own concerns, both artistic and pragmatic, as they relate to the process of designing and constructing one or more of his buildings. The approach of each of these architects differs tremendously: from Norman Foster's space-age technology, so visible in the taut skins of his buildings, to Richard Rogers' mechanistic and structural gymnastics in the design of the Center Beaubourg; from Arthur Erickson's use of structural elements to create powerful sequences of space to Harry Seidler's predominant concerns with exploring various methods of construction.

Others who analyze their own work process include John Johansen, Gerald McCue, Herman Hertzberger, Fumihiko Maki, Cesar Pelli and Kisho Kurokawa.

While it is clear that there is no single answer to the relationship of design and construction, the points of view expressed in this book show just how divergent the possible approaches are. Their words as well as their work are provocative reading for architects, students, and those interested in the built environment.